Putting patient preferences and values back in EBP

Evidence-based practice (EBP) has been the accepted norm in medicine and rehabilitation for nearly 30 years, though exploration began of its concepts in the early 1970s (Zimerman, 2013). EBP consists of three elements: the best available evidence, the clinician’s knowledge, and skills, and the patient’s wants and needs (APTA, 2020). This latter component is also stated as patient perspectives and values (ASHA). All descriptions of the EBP model point to an equal weighting among the three tenets, though most provide little detailed instructions on how to assure the weighting is carried out in that fashion. Many professional bodies established clinical guidelines and pathways to determine how to rank evidence, with case studies and clinician experience at the bottom of the ranking and systematic reviews and RCTs at the top. Clinicians are expected to use their clinical reasoning, expertise, and judgment to apply the evidence appropriately. However, how to go about assuring patient preferences and values are met is a bit unclear.

I have a specific podcast that I am particularly fond of, as the presenter speaks on topics dear to my values (and clicks my bias button continually). On a recent podcast, there was a conversation about applying principles of EBP while assuring the uniqueness of the individual patient was met, something not always addressed in EBP. As the best available evidence requires rigorous trials involving randomized groups, single incidents are often seen as less-than-relevant, though there is a trend toward allowing such individual cases greater weight (Anjum, 2020). While discussing how to apply EBP within such emerging models and how to allow weight to patient perspectives and values, a comment was made to the effect, “well, it is not like we can have our patients choose the intervention.” Really? Why not?

Patients lack the depth of knowledge and experience to build their treatment plan, and if they did, why would they need us? However, can’t they contribute? In my 35-plus years as a physical therapist, I’ve overheard many different ways that clinicians try to assure that patient expectations and values are met. However, most fall short of the 33% contribution mandate of EBP standards. In a manual therapy setting, asking, “how’s the pressure?” seems to suffice for many, while in the exercise-based setting, so much power is given over to the clinician that few questions are asked. Patients often assume that we know the cause of a problem and also know the best way to intervene. Power is given. However, are there better ways to go further in allowing patient input to be equivalent to clinician input?

I once studied with a brilliant clinician who had a deep level of knowledge about how past psychological aspects often led to certain functional problems and applied his manual therapy skillset to remediate those problems. However, I saw as problematic that though psychosocial factors leading to those problems were acknowledged, little if any attention was given to those factors during the intervention. The clinician simply applied what they knew to be necessary for the problem that they palpated. Did the clinician have an impact? Indeed, and their work was published and well-regarded. However, could they have improved their allowance of patient perspectives and values in the therapeutic interaction? Yes, indeed.

How can we elevate that 3rd leg of the EBP model to assure an equal weight is allowed to patient perspectives and values? Many ways, but to start, we can include them more in the decision-making process. In my work, which is to improve function and reduce pain using a manual therapy-based and movement-based blended model, I make it a requirement that my patient fully participates in treatment decisions. This mandate is not always straightforward for the patient to accept, as they often feel ill-informed in treatment decisions. It takes some time to establish both the need for their input and the skillset for them to put this plan into action.

Below is an excerpt from one of my seminar manuals, in which I describe the basics of such a patient-centered model.

Once you have collected their history and complaints and spoken on their functional needs, ask them where they feel their issue. The issue/location could be where they feel the pain, the part of their body where they feel their movement difficulty, where their voice has challenges, where swallowing is impaired, where the tongue gets tight, or whatever brought them to you. Ask them where they feel the problem lies. Some may have no idea, while most will be able to localize the problem area.

• Let them know that the point of this evaluation process is for you to be able to touch, press, stretch, or do something with your hand(s) that connects them to their complaint. You may increase the feeling to a point where you bring it to the edge of the patient’s awareness or even calm the issue to a point where it is barely apparent, but either way, you need to do something with them that they feel relevant. You are looking to replicate a familiar feeling.

• If they are confused by this, or ask, “why do you want to make me feel it?” I suggest that you tell them that it is not your goal to make them worse or to make the problem worse. However, this work’s nature is such that to know that we can help requires us to connect them with their issues. If we cannot replicate the symptom or link them to their problem, both from the periphery (the tissues) and their perception (sensation), then we stand a lessened chance of helping.

• If at rest, they feel nothing, none of their issues, let them know that you may be seeking to allow them to begin to feel it through the therapy process. The concept of bringing their concern to their awareness may be difficult for them, as, for instance, they only notice the problem after doing something. Someone with a vocal strain that only occurs after a performance may wonder how you will be able to replicate the feeling when they have not sung. Someone suffering from back pain that comes on only after standing for a certain length of time may wonder how you will be able to get them to feel something familiar when they have been sitting and have no pain. Let them know that this is your mandate; to connect them with their issue, whether it is present at that moment or not.

• Ask permission to touch them and then place a hand or hands on the identified area. Initially, do nothing; allow your hand to rest on their skin lightly. I will typically then ask them if they feel any of their issues. That gives me an idea if I need to mildly replicate the feeling of the problem or try to reduce it with my stretch.

• Begin to apply a light stretch in the 1-2/10 range on your scale.

• Work in slow-motion; do not move quickly or apply heavy or aggressive pressure. Your pressure might be a lateral

stretch in any direction to the skin or deeper layers, used with a combination of pressure or gentle inward probing. The type and orientation of stretch necessary to connect with the patient’s condition are unique, varying from person to person. Think of this process as one of talking to a person who speaks another language. Each of you has little ability to speak each other’s language, and communication will be slow. It takes each of you a while to find the correct word to communicate an idea correctly, so you work your way through the process until each of you made your point. This process of evaluation is similar. You are trying to find a direction and pressure of stretch in and around the soft and hard tissues, one that your patient begins to feel that you have touched their problem.

• Once you have found a connection, you will need to work out if what you are doing should be continued as treatment. Ask the patient:

• Does this feel familiar?

• Are you feeling a replication or lessening of the issue?

• Does this stretch feel like it might be helpful?

• Is there anything about what you feel that feels like it could be harmful?

• Would you like me to add more pressure? If yes, slowly add pressure until the patient says that now better feel

connected to their issue.

• Finally, once you have adjusted the pressures and direction, ask them if they want you to continue with the stretch.

• When you start to use this work, hold a stretch for 2-4 minutes. During the stretch, you are asking the

patient if they still feel like the stretch is helpful. After 2-4 minutes, slowly release your pressures and retest. Do they

feel different? Have you been able to help them modify the sensation of the issue?

• Depending on your comfort with the techniques, you may now wish to treat more in the same spot or try a slightly

different area. If the patient has felt a change, you might move into the other intervention strategies you use.

• Treating for 2-4 minutes is a suggestion. I spend much longer with this work, often allowing a series of stretches

interventions to a single area take up nearly the entire session.

• No matter if you are using just this manual therapy work or combining it with other interventions, always teach the patient self-treatment. Many forms of manual therapy are too passive; they do not build self-efficacy. I always encourage my patients to follow through with self-stretching, if it feels helpful to them, and increase their movement through exercise, strengthening, or simply moving more. Passivity happens when we do not include the patient in treatment decisions, whether it is through manual therapy or exercise-based models of care.

The original intentions of EBP have been lost, though many feel they honor it. I think we can do better.

- Anjum, R.L., Copeland, S. and Rocca, E. (Eds) (2020) Rethinking Causality, Complexity and Evidence for the Unique Patient. A CauseHealth Resource for Health Professionals and the Clinical Encounter, Springer (open access book).

- Components of Evidence-Based Practice, 2020. APTA.org.

- Evidence-Based Practice (EBP), ASHA.org.

- Zimerman, AL. 2013. Evidence-Based Medicine: A Short History of a Modern Medical Movement, AMA J of Ethics, 15(1):71-76.

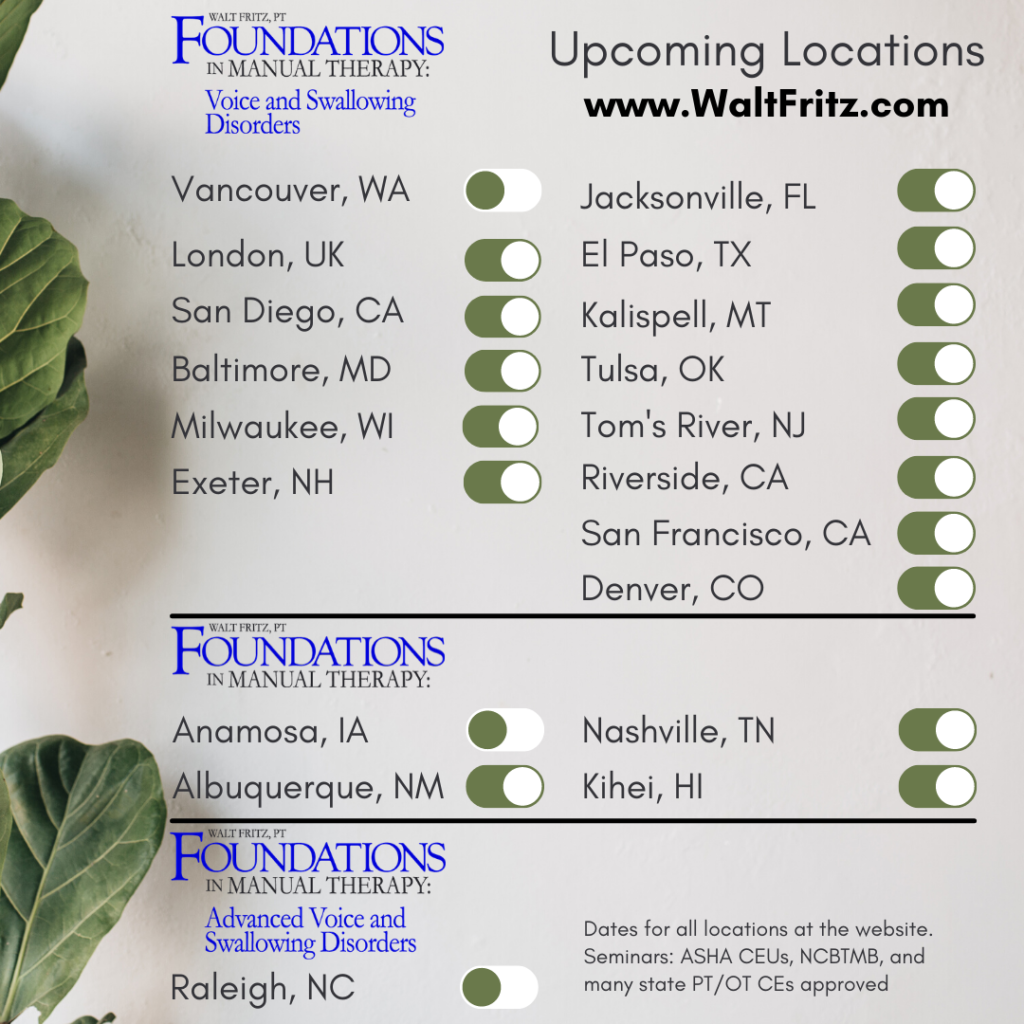

Please consider checking out my upcoming live seminars and online course offerings, including a full hands-on online course. You can find the information here. Also, read up on my in-person seminars at the links in the menu on this page.

So often clients have been conditioned to think their feelings and observations are irreverent. When they begin to discern that in this approach they are a vital part of the prosses and begin freely volunteering information that contributes to solving the origin of the problem and its solution. Example the lady that said the palpation of her neck she felt in her armpit. I was only a couple year into my practice so I told her I would do some research and explore it the next session. Research in my school work book reveled: Omohyoid this muscle will not be taught and you will not be tested on it. 25 years later I know it well as commonly dysfunctional after whiplash injuries.

Omohyoid…such a probable vestige from the past, but still a part of who we are today. However, one source give the omohyoid function in re-establishing breathing after swallowing.

Patient input is so minimized and marginalized by our many shared professions. Time to move forward from this.